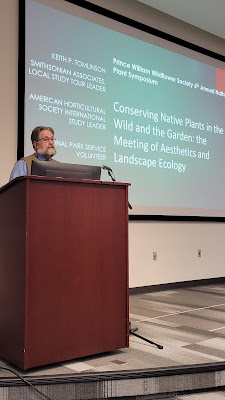

On Saturday

February 11th I delivered the keynote talk at the Prince William Wildflower Society

6th Annual Symposium. This was an honor and great opportunity to

discuss one of my favorite subjects about mixing garden aesthetics with a

further understanding of landscape ecology. Many vocational gardeners, even

relatively sophisticated native plant gardeners, don't have a grasp of

landscape ecology as a basic tenant of supporting conservation in the garden

and in the wild.

Reflecting my own interest, I discussed the origins of our native

plants from preglacial Tertiary Forest distribution, Pleistocene glaciation and

postglacial forest migration from southern refugia in peninsular Florida and

southeastern North America. Through this approach I hope to enhance the general

knowledge of native plant gardeners and encourage them to consider a holistic

approach to the landscape through the increased understanding of paleoecology

and modern landscape ecology.

Landscape ecology is the science of studying and improving

relationships between ecological processes in the environment and particular

ecosystems. This is done within a variety of landscape scales including

biogeography, ecoregions, historical geology, climate and continually emerging

conservation issues.

Concisely, landscape ecology can be described as the science of

landscape diversity as the synergetic result of biodiversity and geodiversity.

In addition, I introduced the concept of Ecoregions. Ecoregions

cover relatively large areas of land or water, and contain characteristic,

geographically distinct assemblages of natural communities and species. The

biodiversity of flora, fauna and ecosystems that characterize an ecoregion

tends to be distinct from that of other ecoregions. Think the Adirondacks, Everglades, the

Sonoran Desert, Ozark Mountains or Great Lakes forests. Currently there

are 115 major ecoregions described in North America. Every single one is unique

and can be on display by landscaping with native plants. Embracing your

ecoregion is fostering a sense of place that makes gardens truly unique while

increasing environmental and aesthetic quality.

The following terms are used routinely in the presentation in hopes of

profiling both Landscape Ecology and Ecoregions.

Floristic- what plants grow where and why

Ecology- Interrelationships of organisms including biotic and abiotic factors

Biogeography- spatial distribution of organisms or biomes

Ecoregions- include geology, landforms, soils, vegetation, climate, land use,

wildlife, and hydrology.

Geomorphology- evolution of landforms/topography

Endemic- small range of distribution, common in island floras

Indigenous- native but with a wider geographic range.

The mid-section of the presentation profiles 25 plants that are unique

or nearly unique to the Mid-Atlantic region. This is based in part on the seminal

book Floristic Regions of the World by Armen Takhtajan. Takhtajan describes a “Floristic

Geography” denoting species that are particularly characteristic of the floristic

regions around the world. Predictably the endemic kingdoms of Hawaii, New

Caledonia the Cape province of South Africa and Canary Islands get a great deal

of attention. But, cosmopolitan continental floras also reveal a great deal of variety,

not so focused on endemism but based on plant diversity due to complex past

migrations and ecoregion distribution.

.jpg)

The last portion of this presentation addresses coalescing environmental

issues that are actively effecting our local and global environment.

Predictably, we discuss climate change and look at possible scenarios for the

mid-Atlantic region where warmer, wetter conditions are expected- punctuated by

occasional droughts. Fall of 2023 was an excellent example of regional drought

complete with local forest fires, mainly in the mountains. We look at plants we

can now grow including Musa basjoo the banana native to Southern Japan. In addition, we discuss the proliferation of various invasive species including naturalized, adventive and introduced.

I also cover rapidly emerging advances in genetic technology. Twenty

years ago, I coined the term MGR for the Molecular Genetic Revolution with Smithsonian

Groups, mainly borne out of new cloning technology. This has now been eclipsed by

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Palindromic Repeats). The current focus of CRISPR

is on various exciting medical applications. In particular, Cystic Fibrosus and

Sickle Cell Anemia among other maladies. I suggest this technology will find

application in the vast world of plant biology and have influence on both crop

production and conservation issues.

Over the past few years work on the American Chestnut has largely

abandoned breeding efforts with the Chinese Chestnut in favor of a tree altered

with CRISPR technology. Thus, a non-crop genetically modified organism (GMO)

focused on conservation and restoration is being planted widely in the

Northeastern United States. This is not without controversy, but recently the

Sierra Club endorsed the effort.

Beyond bringing back near-extinct species, I posit a different, yet

unanswered question. Is it possible CRISPR could be used to alter the

reproductive cycle of various invasive weeds. Could Japanese Knotweed or Stilt

Grass be modified to become sterile and simply fade away over time?

My hope is to encourage planting of regional native species everywhere,

not just gardens but commercial landscapes, city centers and elsewhere. This

relates directly to Doug Tallamy’s focus on food webs in native vegetation and

insect diversity that underlies the ecosystems we depend on. Spanning the

natural history of our native forests in combination with ecoregions, landscape

ecology and geomorphic phenomena I hope to foster a deeper appreciation of our

native flora. Closing with the questions of climate change and genetic advances

should further illustrate the dynamic environmental continuum we are living in- the soon to be coined the Anthropocene.

.jpg)